Review and photos by Faelrin, edited by Suspsy

In 1965, during part of a Polish-Mongolian expedition, a pair of giant enigmatic arms were discovered. The owner of these arms was then deemed Deinocheirus, meaning “terrible hand.” It wouldn’t be until 2014, nearly 50 years after the “terrible hand” was initially discovered when new, more complete material was described, showing the species was stranger than what had previously been envisioned for it. The material from two specimens (an adult, MPC-D 100/12, and a subadult, MPC-D 100/128) had been discovered by a Korean-Mongolian team in the early 2000s, but had suffered losses from fossil poachers. Thankfully, some of the material (skull, hands, and feet) was later recovered and reunited with the rest of the skeleton, specimen MPC-D 100/127, the adult. Combining the material from all three known specimens allows a near complete image of this giant theropod: a giant billed, hump-backed ornithomimosaur. The new material also helped give insight on the diet of the animal too, as specimen MPC-D 100/127 was preserved with gastroliths and fish scales within its stomach contents, showing it was likely an omnivore.

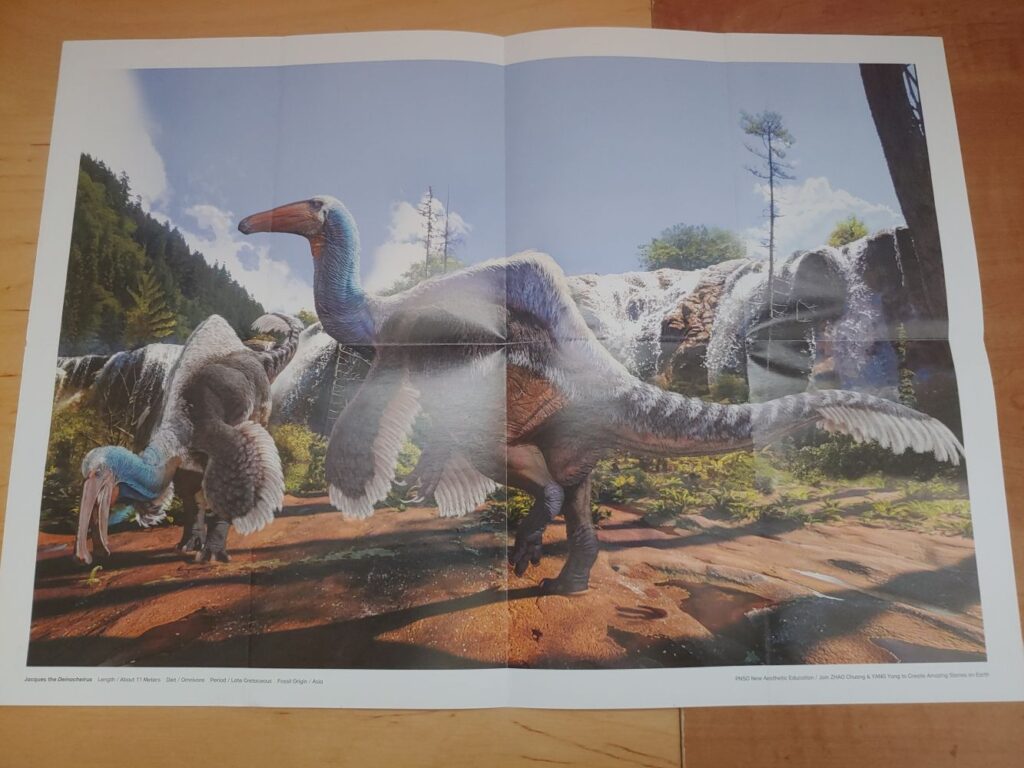

Last year, PNSO released a rather striking figure of the strange beast that was Deinocheirus. How appropriate considering it aired in the highly acclaimed Prehistoric Planet documentary a few months prior, in Episode 3, “Freshwater.” The model is #64 in the Prehistoric Animal Series, and has been named Jacques. Like the other figures in the series, it is packaged in a box, and comes with a stand and poster. The poster features an interesting scene depicting two Deinocheirus feeding and walking, painted rather closely like the figure.

Focusing on the figure itself, the sculpt captures all the iconic features and proportions of this giant strange ornithomimosaur, with its duck-like bill, humped back, and a shaggy coat of feathers similar to the likes of an ostrich. The neck, belly, and legs of the animal features bald skin, and the tail features a plume of feathers. The hands and feet of the figure are covered in fine scales, just like what is commonly depicted on other theropods. The lower jaw is articulated.

The coloration of the figure is perhaps the most eye-catching aspect aside from its unique features. The neck is painted in a bright blue, and the tip of the tail continues this coloration in the form of stripes. The body is primarily brown, but there is a cream patch that continues into the tail in the form of striping. On the promo pics of this figure, the striping on the tail interchanged between brown and blue, but on the final version, the brown is replaced by the blue coloration. If I had to pick just one, I ultimately prefer the final production coloration, although either would have proved satisfactory. The bill is a yellow shade and covered in a glossy sheen to replicate a keratinous covering, a feature for which there is fossil evidence. The measurements PNSO have given this figure is 12.5 cm/4.9 inches for the height and 29.2 cm/11.5 inches for the length. This puts this figure at approximately 1:37.6 scale using the 11 meters/36 feet estimate for the length of the largest specimen, MPC-D 100/127, sitting nicely in between 1:35 and 1:40 scale, whereas the longer estimate of 11.5 meters puts it closer to 1:40 scale. The skull of MPC-D 100/127 was measured to be about 1.024 meters/3.36 feet long, and on PNSO’s figure, it measures to be about 3.81 cm/1.5 inches, giving it a scale of approximately 1:26.8. So it may be a bit oversized if that’s all correct. These calculations were made with an online calculator so take them with a grain of salt, and if anyone can provide more accurate estimates, please comment below.

Regarding the feathers, it is currently unknown whether or not Deinocheirus would have had or needed feathers, due to its large size (as has been suggested for Tyrannosaurus in recent years). I think PNSO giving some portions of the animal bare skin like on an ostrich helps balance this out, versus on some older models like the ones by Safari Ltd. or CollectA that depicted it as completely feathered. There is evidence from one of its more derived relatives, Ornithomimus, that was feathered. In fact, there are numerous specimens that show feathers from the neck, arms, back, legs, and tail. From one of the specimens, there is also evidence of bare skin on the legs and the underside and belly region, so PNSO made the right call to implement the bare skin in those regions, if not the speculative addition of the neck being bare as well. It’s probable that they based these features off the evidence from these specimens of Ornithomimus, if not extant birds like the ostrich.

The arms also feature fluffy wings, not too dissimilar from an ostrich’s, although I’m not sure how accurate it is for there to be a mix of long and short pennaceous feathers. I’m also not entirely sure if the feathers on the arms of Ornithomimus and other ornithomimosaurs were attached like in dromaeosaurids and similar non-avian dinosaurs, where the primaries attach to the second digits, so I’m not sure if what PNSO has sculpted here is accurate or not. I do think it looks appealing nonetheless. I could not access the papers regarding the Ornithomimus fossil material as they were paywalled. As ornithomimosaurs were flightless, their wings would have likely served for either incubating eggs, mating displays, or insulation. Deinocheirus is also known to have a pygostyle on the end of its tail, which in birds and related theropods serve as an attachment point for feathers. Other unrelated animals like plesiosaurs have also been found with pygostyles, so it isn’t a definitive way to know if it could have served as an attachment point for feathers. It can only currently be inferred based on relatives like Ornithomimus and other theropods.

Moving on to other aspects of the anatomy, the skull on the figure captures the spoonbill-like appearance of the bill, where the skull is narrow behind the tip of the jaws and then widens towards the back of the head. Similarly, the arms and hands capture the formidable look of them. The claws are sharp, with the largest on the first digit. The digits are all similar in size, reflecting the fossil material. Moving on to the feet, when compared to the similarly sized Tyrannosaurus, Deinocheirus had proportionally smaller feet which is reflected on this model, although the digits themselves had similar proportions like the former to help with the weight distribution. PNSO has also sculpted the toes splayed out in a similar manner to Tyrannosaurus. The bottoms of the toes are sculpted with fleshy pads, as on birds and some non-avian theropods. I’ve gone a bit more into detail about this matter in my recent Beasts of the Mesozoic Yutyrannus review. Altogether, there are three toes, similar to an ornithopod, which ornithomimosaurs are known to possess, having lost the first digits. In fact, Deinocheirus had particularly hadrosaurid-like feet, with blunt claws. Hadrosaurids were a derived group of ornithopod dinosaurs that animals like Parasaurolophus belonged to, and with Deinocheirus having convergently evolved similar feet, it is yet another one of the many unique and strange adaptations this animal had, adaptations that set it apart from its much closer relatives.

Despite being covered in feathers for the most part, the figure is also sculpted as being rather muscular. This can easily be seen on the underside of the pubis and tail, for which there is supporting fossil evidence, and a feature that would have provide support for its larger body size, never mind the large unique camel-like hump on the back.

Now, one more thing to touch upon is the where and when Deinocheirus lived. It was from the Nemegt Formation, located within modern day Mongolia, and lived during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, 70 million years ago. The ecosystem of the Nemegt Formation was lush and humid with rivers and lakes. Flora included araucarian trees and duckweed. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Deinocheirus include Gallimimus, Prenocephale, Tarbosaurus, Tarchia, Saurolophus, Therizinosaurus, and others. There’s even fossil evidence from the holotype specimen of Deinocheirus: tooth marks on the gastralia showing its remains had been fed upon by Tarbosaurus. PNSO has also made figures of Tarbosaurus, released in 2021, and Therizinosaurus, released right after Deinocheirus. This allows one to have a complete trio of the large theropods from this formation. Thankfully, they are all more or less to scale.

This is easily my favorite model release from PNSO last year, and quite possibly my favorite of all 2022’s releases, despite some heavy contenders like the Eofauna Diplodocus and the Beasts of the Mesozoic Fan’s Choice Medusaceratops repaint. It might even be my number one favorite from the company, with their Parasaurolophus a close second. While I quite liked the 2017 Safari Ltd. model of this genus (that I also previously reviewed), this one hits on so many notes, between how the integument, the feathers, and the skin were sculpted, and the contrasting vivid blue and earthy browns and creams. I would be surprised to see another model of this genus excite me as much as this one has (although perhaps a Beasts of the Mesozoic/Cyberozoic version might, if it is made someday). As a theropod without teeth, this also avoids falling into the controversial trend of lipless theropods that PNSO has continued this year, such as with their recent carcharodontosaurids and tyrannosaurids. This model should be available from Happy Hen Toys, Everything Dinosaur, PNSO’s Amazon, and AliExpress stores, and anywhere else that sells PNSO models, and I highly recommend it. I also recommend the Kaiyodo Ornithomimus that I’ve used in one of the comparison images taken for this review.

Disclaimer: links to Ebay and Amazon on the DinoToyBlog are affiliate links, so we make a small commission if you use them. Thanks for supporting us!

Five one star votes to date, September 10, 2023. What does that say about the mentality of some voters (fortunately a very small minority)?

This was my favorite release from last year but the more I think about Deinocheirus the more I think that such extensive feathering was unlikely, which you do touch upon. Shaggy Deinocheirus is somewhat of a trope now but since this is such a massive animal living in aquatic or semi-aquatic habitats it really seems unlikely that it was so extensively covered. Poor thing would be practically waterlogged while living in a humid, hot environment. Anyway, still love the figure, great review!

Temperature estimates for the Nemegt Formation actually indicate it was on the cool side.

Can’t find anything about the temperature, only that the Nemegt formation was wet. But even if it was on “the cool side” that would only mean that Deinocheirus was then wet and cold, which might be worse than wet and hot. Basically, if it is wet then it probably didn’t have or need a dense coat of shaggy feathers.

According to Eberth 2018 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031018217305771) the Nemegt was somewhere between arid and seasonally wet. The position of Mongolia was similar to its modern one, but in a warmer baseline climate. I think a coat of feathers at least on its upper surface to prevent sun damage is pretty plausible.

Anyway, nice review, Faelrin!

The temperature was given in the supplementary information of the tyrannosaurid integument paper, which is no longer be available as far as I know. Sea otters have dense fur to insulate them from cold water, could the same not apply to Deinocheirus and feathers if it had them?

I don’t think the marshes and swamps inhabited by Deinocheirus are comparable to the generally cold waters of the north Pacific coast.

I’m not suggesting that Deinocheirus didn’t have feathers (though maybe it didn’t) I just don’t find the shaggy coat of many reconstructions realistic, like this one or the one in Prehistoric Planet. Emphasis on shaggy. There may have been some waterproofing involved but if so I would like to see the reconstruction look more how you would expect that to look, dense and smooth, more penguin or duck-like than emu. Those long plumes on the arms don’t look waterproof, they look like a burden for an animal that was perpetually wet.

Beautiful, graceful rendering of the “fully feathered” reconstruction.

One of PNSO’s best efforts to date.

Great and very professional informative piece.

Really enjoyed reading and learning.

Huge 10 out of 10.

Regards.

Dennis

this is a cool figure, but I’ll be sticking with the Safari version. Side-by-side the Safari figure looks comparable in build and proportions, if just smaller