2023 has been a busy year of theropods for PNSO, having released a dozen large predators back to back over the year’s course. Before some collectors started to feel inundated by steady flow of flesh-eaters, however, near the front of their lineup PNSO released Mungo the Meraxes, the first-ever appearance on the toy market of a remarkable new discovery among giant predatory dinosaurs. First discovered in 2012 and described a decade later in 2022, Meraxes gigas (essentially meaning “giant dragon” – the genus name honoring a character from George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series) is one of the best-preserved members of the carcharodontosaurid family. The remains included complete hindlimbs and a nearly complete skull among numerous other bones, helping paleontologists answer many questions about carcharodontosaur anatomy while also presenting brand new ones.

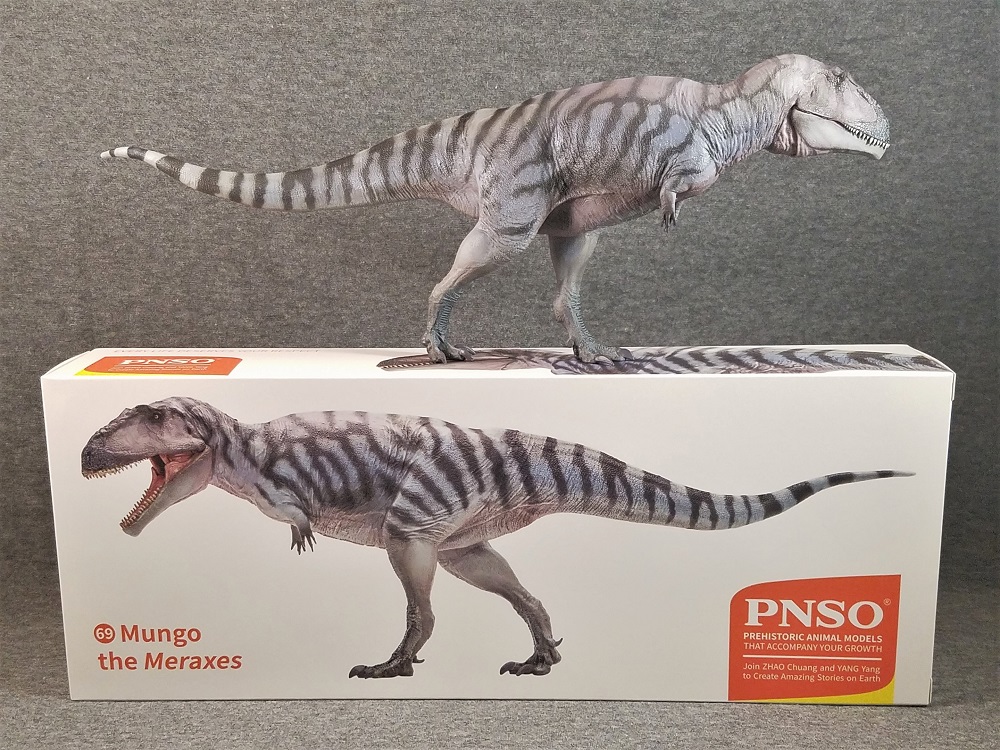

Nicknamed Mungo, PNSO’s Meraxes is the 69th official figurine in the Prehistoric Animal Models series. Mungo was released in between two fellow carcharodontosaurs – a revised Lucas the Giganotosaurus from the Dinosaur Museum series, and Mila the Mapusaurus in the Prehistoric Animal series. Both of these genera were younger geologically, but grew even larger than Meraxes in life. The model measures 30 cm (11.75 in) long straight from nose to tail, or 33 cm (13.25 in) long measured along the curve of the spine. Estimates for Meraxes’s life size sit between 9-10 meters, or possibly as high as 11.6 meters; depending on the life size, the PNSO model hovers around 1:30-1:35 scale. The skull, however, fits specifically in 1:28 scale – 4.5 cm (1.75 in) to the fossil skull’s 1.27 m (4.2 ft) – even though the overall proportions of the model match the fossil remains very closely. My best guess is, the discrepancy in scale lies with subtleties in reconstructing the premaxilla (ie the bone which makes the tip of the snout) or the quadratojugal (ie the back of the skull where the jaw attaches) – neither of which was fully preserved in the fossil remains, to my knowledge.

Meraxes’s skull was massive, but its arms were minuscule – a common trait in giant theropods. The figurine captures the little arms and also the large shoulder blades anchoring them, contrasting the small dimensions with substantial musculature. The three fingers are different lengths, with the thumb being appropriately shortest, based on other carnosaurs. The torso is narrow, but deep; its lowest point is at the pubis bone of the hip, level with the knees. The legs are slender but muscular, and the feet bear the unique traits seen in the preserved fossils. The first toe, although raised, is surprisingly large and curved. Even larger and more surprising is the second toe, tipped with a keratin-enhanced nail reminiscent of a modern cassowary bird’s weapon. Such a feature was unexpected by the paleontological community, and its functionality remains unknown for a creature of this size. Regrettably, this enhanced toe does not guarantee improved stability of the figurine; mine was able to stand beautifully for a month or two, but has since become very sensitive to balance without a stand for assistance.

Carcharodontosaurs were leaner in build than a Tyrannosaurus, but would have nonetheless been strong and muscular animals. Meraxes is reconstructed with a sturdy tail and a bulging caudofemoral muscle at the base, as is appropriate but still sometimes overlooked in theropod reconstructions. The figurine looks fit and trim, while avoiding a physique that would look exaggerated for effect. The uniquely concave shape of the fused hip vertebrae is visible, and certain contours of the skull bones are evident as well, but nothing feels shrinkwrapped about this design. The choice to leave the upper teeth exposed instead of sheathed in lips may be contentious, but the teeth are reasonable in size and look firmly rooted in the mouth, so the effect is better achieved than some of PNSO’s previous bare-toothed theropods. As a side note, the tooth count in the maxilla seems to be short – about 14-15 pairs instead of 18 – but I think the missing teeth would be in the back of the mouth, and may have simply been too small to visibly sculpt. The teeth are quite finely detailed already!

The front of the snout is adorned with large irregular scales, likely referencing studies on tyrannosaur facial features. These large sensory scales transition to smaller, rounder scales along the sides of the face and progressing down the body. The lacrimal horns extend seamlessly down the nose as keratinous ridges, pronouncing the silhouette of the animal’s face. Along the torso and back, there are larger rounded scales scattered in irregular rows – a speculative feature, but one which enhances the figure’s textile details in a subtle manner. PNSO’s models have come to excel at fine detailing, which makes their figurines a delight to handle. Skin folds and wrinkles highlight the body’s joints and shifting inner anatomy as the animal moves, presenting a reptilian character that looks extremely lifelike. Details of the legs and feet, meanwhile, are more avian, with robust bones and ligaments layered by scutes on the fronts of the feet and toes. Nostrils, ear holes, and a minute cloaca are all carefully sculpted but not over-emphasized. The tail bears the same scalation as the torso, although PNSO could have tried adding larger scutes along the underside like those preserved in Meraxes’s early relative Concavenator. A small missed opportunity, perhaps.

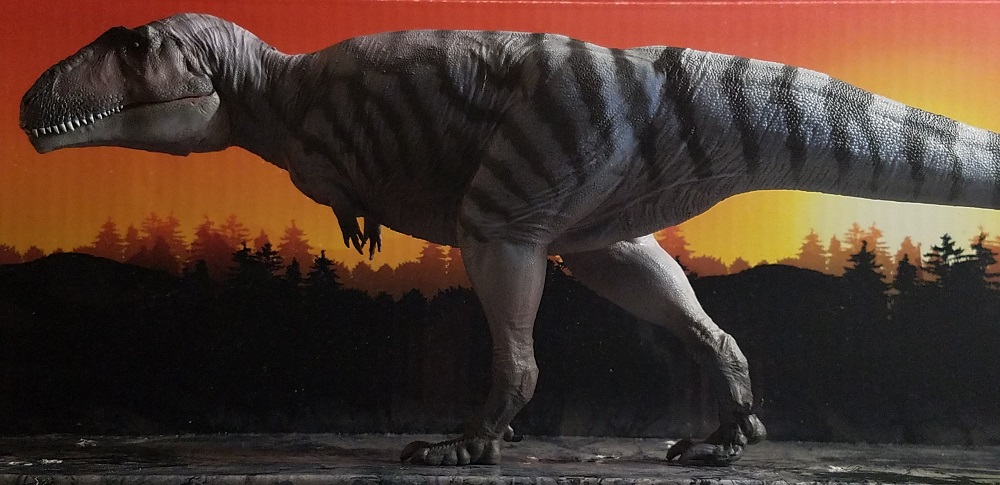

Mungo’s most striking feature as a Prehistoric Animal Model is its coloration. Mungo eschews the typical browns and yellows of its contemporary model theropods in favor of a remarkable striped pattern that almost appears grayscale at a glance. While the interconnected rows of stripes are genuinely a dark charcoal gray, the rest of the body is in fact washed in subtle hues of magenta and blue, almost pastel in tint. The face has a purplish flush, fading to pink along the neck and separated by the striping into sky-blue on the flanks, the two colors paralleling each other down the tail. The undersides diverge back into pink/magenta, with occasional lightened patches that have an almost greenish tint. It’s a remarkable color scheme and I’ve never seen anything quite like it among toy theropods; it’s a sure standout among PNSO’s offerings, at least.

Mungo the Meraxes is a beautiful model of an important new discovery in large theropod dinosaurs. Collectors may be feeling theropod fatigue from PNSO’s offerings this year, but Mungo is a splendid model deserving of attention for its unique traits, as a collectible and a genus. The model should be available for purchase from all retailers selling PNSO products, including Everything Dinosaur, Happy Hen Toys, and PNSO’s own official Amazon and AliExpress shops.

Support the Dinosaur Toy Blog by making dino-purchases through these links to Ebay and Amazon. Disclaimer: links to Ebay.com and Amazon.com on the Dinosaur Toy Blog are often affiliate links, when you make purchases through these links we may make a commission

Safari Giga a király.(a Carcharodonthosaurus modellek közül)De persze ez is tetszik.

Not too interested in PNSO’s carcharodontosaurids but this the most attractive of them. The exposed teeth don’t bother me much here, at least they don’t look like they’re rotten and sliding out of its face! Great review and pictures, as usual!

The striking pattern definitely helps this one stand out from its many relatives on the shelf. Nice review!

Fantastic review. Glad to see this one finally up here on the blog.

No skin covering for the teeth (aka “No lips”)?

PASS!

Next, please … :>)