Like many readers of this blog, one of my favorite things to do when visiting a new city is to check out the local natural history or science museum. For getting a sense of the scale and proportions of ancient life, nothing beats seeing specimens, or even reproductions of specimens, up close and personal. And what better souvenir can you ask for than figurines representing some of the animals you saw during your visit?

Sadly, I’ve never been to Toronto, but I was able to bring a little bit of its Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) to me via the “Primeval Predators” kit, a set of five brightly colored toys representing animals from Canada’s famous Burgess Shale. The Burgess Shale is one of the most famous fossil localities in the world, giving an unparalleled glimpse into Cambrian ecosystems, even preserving creatures with no mineralized tissue that would have decayed too rapidly to fossilize anywhere else. This kind of exceptional environment is called a lagerstätte (pronounced “law-guh[r]-shtay-tuh,” pl. lagerstätten), and the Burgess Shale is the quintessential example. Let’s take a look at these five denizens of Cambrian Canada:

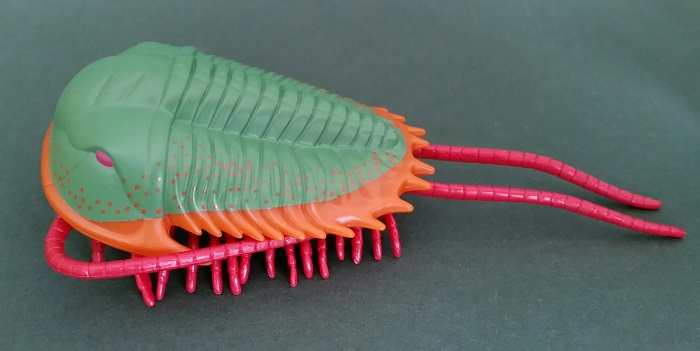

First up is Olenoides serratus, a common trilobite known from over 200 specimens. This figure is about 8.5 cm long, making it approximately life size. It correctly shows the sharp, pointy edges that give it its specific name, as well as the long, thin antennae. The antennae have too few segments, but some simplification for a toy strikes me as acceptable. There are, correctly, seven jointed thoracic segments, as well as several fused segments (collectively, called a “pygidium” or “little rump”). Two threadlike appendages called cerci (sing. “cercus”) emanate from the posterior end of the figure, a feature that distinguishes Olenoides from other trilobites. Some living arthropods also have cerci, which may have sensory or mating functions, but their function in Olenoides is not known. Considering how often trilobite toys are just generically called “trilobite,” ROM deserves praise for making a toy that is a faithful, if stylized, rendition of an identifiable trilobite species.

The big gun in the set is this “Laggania.” The name “Laggania” is no longer in use, having been assigned to a detached circular mouthpart. At first, the disc-like structure was proposed as a possible jellyfish, but it later became clear that it belonged to another animal named in the same exact scientific article: Peytoia. Peytoia is a relative of the ubiquitous Anomalocaris, although it is thought to have been a filter feeder rather than an active predator like its larger relative. Anomalocaris is sort of the Tyrannosaurus of the Cambrian: almost every company that bothers to make Cambrian creatures starts with it. For that reason, it’s refreshing that this set includes a generally ignored relative. This toy shows the “arms” under the head, bearing filaments that would have helped it filter particles of organic matter out of the water. The circular mouth (the “Laggania” part) is just barely visible in this photo. At about 13.5 cm long, this is about 3/4 life size.

If Anomalocaris is the Tyrannosaurus of the Cambrian, Opabinia regalis is the Triceratops. Lots of Opabinia figures exist, although this one may well have been the first, as the information cards that come with these figures all say “© 2000,” which would mean they came out a year earlier than Kaiyodo’s Opabinia. For being over 15 years old, this figure holds up quite well, which is a testament to both the good quality of the toy and the exceptionally good information preserved in the fossils. It has the correct number of segments and a plausibly shaped and oriented anterior appendage. At about 10 cm long, this is about 1.5× life size.

Tiny, wormlike Pikaia gracilens is often of particular interest to people, because it may be a close relative of our direct ancestors. Pikaia has what appears to be a notochord, which humans have as early embryos, later being segmented to become the disks between our vertebrae. It also has pigment spots that were initially interpreted as eyes (the bright red spots on the underside of the figure’s head). These spots have since been reinterpreted, and most paleontologists no longer consider it to have eyes, but this figure was produced before that reinterpretation. The toy also shows the row of tentacles, the one anatomical feature that Pikaia has that is unknown in true vertebrates, and perhaps represents evidence that it was a dead-end offshoot of our early family tree, rather than our direct ancestor. At about 7.5 cm, this toy is about 2× life size.

Finally, we come to Wiwaxia corrugatus, a strange bottom-dwelling animal with scaly armor and spines. The armor was not mineralized, but made out of a hard carbon polymer (hey, the toy is also made of a hard carbon polymer!). It was probably a stem-group mollusc, meaning that all living molluscs are more closely related to one another than to Wiwaxia. The underside had a slug-like foot, with which it crawled along probably eating things out of the mud. This version is about 7.5 cm long, or roughly 2.5× life size.

This set is a really nice cross-section of the diversity present in the Burgess Shale. If the accompanying information cards are correct that these were produced in 2000, then all or most of these are the first figures of their species. However, it also means it’s probably too much to hope that the ROM will make additional sets from other Canadian fossil deposits (such as the phenomenal Ordovician sites in Manitoba). If they were going to make more toys like this, I think they would have done so by now, but as far as I’m concerned, an expansion of the “Primeval Predators” concept would be quite welcome. These toys are stylized, but not quite cartoonish, and brightly colored to the point of being psychedelic–but the Burgess Shale might well have looked pretty psychedelic in life. I’d recommend this set to anyone who likes invertebrates, Paleozoic animals generally, or the very strange. You can still get it directly from the Royal Ontario Museum web site, and presumably in the museum’s gift shop as well.

Disclaimer: links to Ebay and Amazon on the DinoToyBlog are affiliate links, so we make a small commission if you use them. Thanks for supporting us!

I have a second-hand set of these toys available for sale, if anyone is interested. My son has decided he’s moved on to other interests. We have the complete set of figures, but I’m still looking for any papers/description that may have come with them. They still are in very good condition, due to the excellent quality of the figures in the first place. Please reply to discuss price. I’m open to offers – but shipping will not be included. Shipping will be from Ontario, Canada. If this isn’t the place for this posting, I apologize.

It is okay for you to post here, but you’re more likely to get a response on the Classifieds section of the Dinotoyforum: http://dinotoyblog.com/forum

I’m glad to see these are still available for purchase. Might have to pick this set up later in the year though (broke right now). However I am wondering how purchasing this will go (and cost) since I’m in the USA. I’ve never purchased anything overseas, except on ebay before.

The shipping wasn’t too bad, actually.

A Pikaia tetszik a legjobban!

Hope you do get to visit the ROM someday. May want to hold off for a few more years until they complete the Dawn of Life gallery.

http://www.rom.on.ca/en/support-us/sponsorship-opportunities/the-future-gallery-of-early-life

I actually think I might be there later this year for work, but that new gallery would give me plenty of reason to go again!

One question since I am interested in these figures. Are they made of PVC (plastic) or are they of another material, even breakable?

I am to order them but first of all I want to make sure if it is perishable resin material or other breakable material if it contacts the ground. Or it is of an unbreakable material by an accidental fall to the ground.

Anyway his figures are extraordinary.

They are sturdy plastic, not fragile at all.

Thanks for the info. I have already ordered them. More figures for my collection.